The two women clasped hands. “Thank you,” Claudia whispered, “For saving me.”

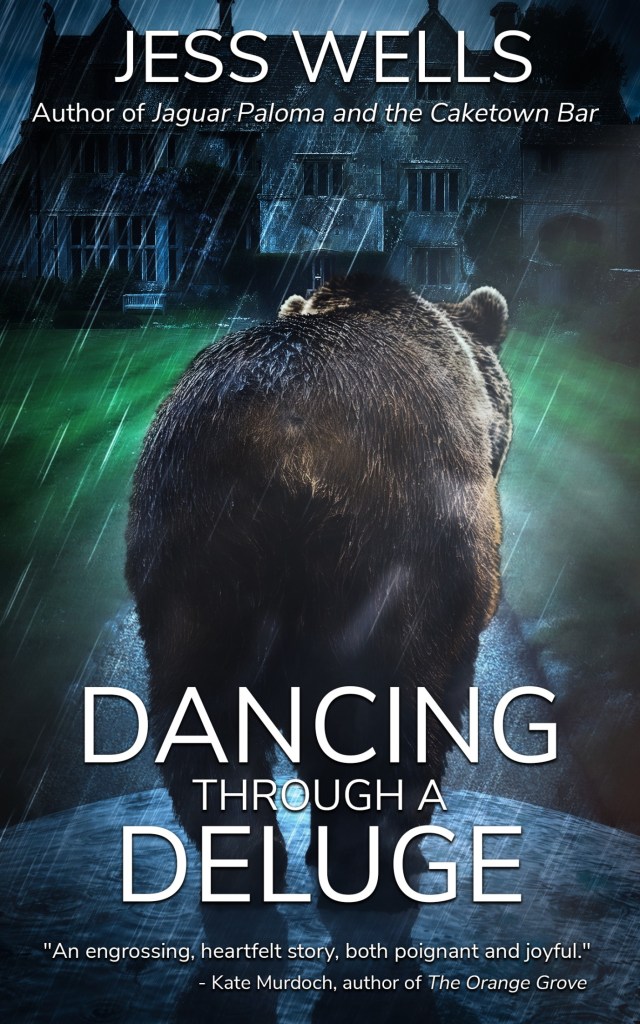

Dancing Through A Deluge – Jess Wells

If you’re a fan of historical fiction, you really need Jess Wells on your radar! I recently had the pleasure of reading the latest from Jess, Dancing Through A Deluge. It’s the story of MT, a nun who has survived the horrors of the Black Death. She stumbles into a ransacked manor house and is mistaken for the baroness. And what ensues is a story of community building, of freedom and hope. About doing what is right and using powers for good. It is a wonderfully uplifting read but definitely has plenty of heartbreaking moments too. I’ve loved finding out more about Jess, and really hope you enjoy reading too! (You can read my review of Dancing Through A Deluge here!)

1. What inspired you to choose the 14th Century/the Black Death as the setting for your story?

It’s partly because we had just emerged from the Covid pandemic. The silence of the city when we were in lockdown was startling. In my previous novel, Jaguar Paloma and the Caketown Bar, residents of a floating village face a drought, which Californians had lived through for a full decade. The anxiety of it was profound. But three facts spurred my imagination for this book: the Black Death killed so many people that villages were just abandoned because there so few survivors. People on the move create a good plot and people trying to reinvent themselves try on different personas; their growth is expected, their backstory is not quite as important.

The second fact is that the Black Death caused enormous upheaval in the European social structure. Labor was in high demand and short supply which threatened the power of the gentry because fallow land produces no revenue. Royalty struck back, of course, and passed the Ordinance of Laborers in 1351 which mandated that serfs who were found off the manor could be forcibly returned or imprisoned. Pretty shocking stuff and the reason the book opens in 1351. The third is an anecdote so vivid that it drove the book for a while: most grain mills were owned by the church or the gentry, but group of peasants rebelled and created small, family-sized millstones. The bishop rode through the village and confiscated all the millstones and had them cemented into the floor of the church to remind the peasants of who was in charge. The workers stormed the church and tried to chip out the millstones. I love that visual of trying to take back power.

2. How did you approach the research for this book? Did you find out anything that surprised you along the way?

I love that historical settings are our world, but not really. Almost like magical realism: it’s real, but different. Surprising. For example, I knew that individual homes didn’t have ovens at that time, that the bake house was set slightly away from the village to prevent fire from spreading, but I didn’t know that people came to the bake house with their dough ball already created and then sat and waited for it to bake. What a great meeting place; a great way to gather characters and then send them on their way. An itinerant baker wheeling a clay oven from village to hamlet? Who knew! The way salt was collected really shocked me. The Master of the Hounds and the use of dogs on a manor was surprising. Even realizing that the wetnurse was privy to all sorts of insider information.

When I learned that rabbits had been valuable livestock in the Middle Ages, especially in rocky country where crops were difficult to grow, I assumed they would be housed in a big barn, like a modern chicken farm. Pictures of rabbit warren lodges made me assume that the rabbits lived inside the stone buildings. Nope. Rabbit warrens were enormous spans of land where the rabbits lived protected by moats and their tunnels were fortified with pipes or rock by the warrener. The stone building – the warren lodge — was a veritable fortress of stone walls set deep into the ground with narrow slits for windows. The pelts were very valuable items (think ermine or mink) so preventing robbery was paramount. The pelts were processed, dried and stretched on the first floor, and the warrener lived on the second floor above the workshop. It’s all very fascinating to me.

3. Did you face any challenges in capturing the essence of resilience and hope in such a turbulent era?

It’s one of the reasons that the book is set after the plague. I didn’t want to write the horror and fear. The survivors have demonstrated their resilience and believe that the worst is behind them. The turbulence is alluded to, described briefly, and then the more nuanced story can begin.

4. How did you weave the themes of strength and freedom into a time period that often suppressed these qualities?

All people in all eras desire freedom and require strength to survive. Also, all stories require tension and so the struggle to retain one’s freedom in the face of systemic oppression lends itself to the story. With that said, though, historical fiction based in the Middle Ages is going to be inaccurate specifically as it relates to freedom and power. While women certainly had agency, the majority of them didn’t have much, but it gets very boring writing and reading about powerless women for the sake of accuracy. And having more than one comment from a man about the oddity of a powerful woman is just jarring to the story and insulting to the reader.

Additionally, the Medieval period was also a violent time which is unpleasant to read about, as well as a time when people were very religious, which doesn’t interest me at all. That means that you are writing about independent, non-religious women who are able to escape much of the endemic violence. You strive for accuracy in so many aspects of the work, but that core conceit is necessary.

5. The theme of the book is ‘what happens when people are offered what they have always wanted.’ How would you explain this?

I’ve been surprised by people’s reaction to their own success. Some don’t feel worthy; some can’t see that they’ve actually succeeded, as in wrestling with the angel. Some become voracious and just want more regardless of their triumph. Others have been angry over their failure and blame others, only to discover that they could have been successful much sooner if they hadn’t spent their time being angry. And then there are some who have devoted so much of their life to being plagued by their own guilt and failure that the specter of their guilt almost becomes a companion, and the void that is presented to them when they are successful is so frightening that they refuse it.

6. Were there any particular relationships in the book that you found most challenging or rewarding to write?

The men were more difficult than usual in this book. Jacob, the developmentally challenged young man, was originally going to be the protagonist, but I couldn’t keep that voice going. And it was important that he seemed old enough for consent. Simon was tough because I didn’t want him to be one-sided in his negativity. He needed ‘a moment of grace’ as they say. And I wanted it to be clear that Percy was held back by his own lack of confidence, his refusal to see his own accomplishments, but I didn’t want him to seem like a whiner. Honestly, all characters make a writer walk on a knife’s edge.

7. What do you hope readers will take away from your characters’ journeys?

It’s helpful to let go of your preconceived notions of success. Things don’t have to look a certain way. For example, you don’t have to be a mother through a certain process. Success is possible if you are flexible about how it manifests. The same with failure. Claudia felt like a failure because she couldn’t bear a child, but she could be a very successful mother. I want readers to look at their own lives and see how many of the things they think of as failures are really successes in a different form. Most importantly, though, I want readers to ask themselves what they would do if finally given what they had always wanted.

8. What are some of your own favourite books and authors? Are there any books that inspire you to write your own stories?

Gabriel Garcia Marquez is my favorite author: he was the inventor of magical realism. I love reading stories that are rich and evocative, like Salman Rushdie’s early work, and Louise Erdrich. Beautiful language, vivid scenes. Honestly, though, I spend almost all of my reading time on non-fiction, researching history. First the Middle Ages, then trying to find egalitarian societies in the distant past and for a while reading on Paleolithic times. Everything fascinates me, except math.

9. What are you currently working on? Is there anything you can share with us?

It usually takes me about a year to come up with something new to say but just recently I read some factoids that captured my imagination. That’s how I usually start: finding some fact in a history book that is so evocative and surprising that I have to dramatize it. That doesn’t mean that they all work out: Dancing Through a Deluge includes ideas that I developed for a book in 2014 that didn’t get off the ground. A decade later! One time I developed an idea, did the research, created the outline and just as I was ready to start writing I got an email from a woman who had just published a book on the exact same topic from the same point of view! I had to throw all that out and find something else.

10. What’s one piece of advice you’d give to new authors?

Get your priorities in order so you stop wasting time on trivial things like dinner parties, walking the dog four times a day, decorating the house for every holiday. You don’t need to have a pristine house or a high-maintenance garden. I found it helpful to actually keep track of the number of hours each day I spent on my writing to make sure it was balanced – in my case with freelance work. You also have to be very clear with significant others about your intentions. Just tell them that your writing is very important to you. Carve out Sunday morning for your writing and stick to it, even if you’re not working on something. Close the door. Do not allow them to interrupt you. Unless you have children, there’s really no excuse for not dedicating — at the very least — three hours on Sunday to your work. I would also be concerned about the amount you read. Yes, you have to understand what good work sounds like, but living in a dream world through someone else’s writing dissipates the desire to create a dream world of your own.

About the author

Jess Wells is the author of seven novels and five books of short stories, as well as the editor of anthologies of social commentary. She is the winner of the Nautilus Silver Prize for Small Press Fiction with a Social Impact, Bronze Winner of the Foreword Indies Awards, a four-time finalist for the national Lambda Literary Awards, a member of the Saints and Sinners Literary Festival Hall of Fame, and a recipient of a San Francisco Arts Commission Grant for Literature.

Her books are sold through all online distributors and her audio books can be found on Spotify, iTunes, and Audible, among other locations. Her work has been included in more than three dozen anthologies and literary journals, reprinted in the United Kingdom and translated into Italian and Dutch. She has taught at literary conferences and teaching locations across the U.S. Visit her website at www.jesswells.com.

Want to be under the spotlight?

Fancy answering a few questions to allow your readers to get to know you better? Please do get in touch! 😊 You can see other author interviews here.

One Comment Add yours